This blog post is part of a series of reflections on the Corona virus crisis and the immediate transition from my face-to-face courses to online classes.

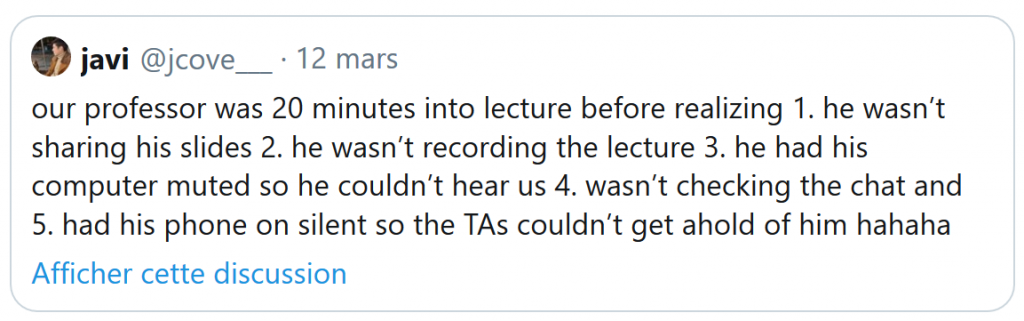

dealing with a 21st century class…

After general thoughts, let’s move on to a field report. Last week, I had the opportunity to test different online teaching setups. I will talk more specifically about 2 experiences, the first one and what I learned from it, and the last one, with all the modifications I tried to put in place to alleviate the initial disappointments.

This post will cover the first experience, or the Dr. Jekyll effect.

Some background: this course was a course shared with one of my colleagues. She was in charge of the first half (1h30), then I took over for the second half (1h30). My part consisted in debriefing a case that the students had previously handed in. This meant showing a few of their cases and commenting on them.

Before the class

A classical (face to face) needs preparation, of course. An online course takes even more preparation, in at least 3 distinct directions that can take a lot of time.

- First and foremost, there is the technological aspect. I had opted for a solution that was both simple (to follow the 2nd law of pedagogics) and ambitious, because it required juggling between several applications: Zoom with screen sharing, and Google documents. The first piece of advice I could give is to really do some training « like in real life » before the class. This allows to discover things that afterwards seem obvious, such as taking the precaution of opening all the necessary documents before the course, so that screen sharing can be done immediately, without having to wait for a given application to be launched, or a document being loaded.

- Communication with students. According to my first law of pedagogics, I had resolved to maintain regular communication with the students. As a matter of fact, there was no need to push in this direction: the implementation of the online course required many types of interactions with the students before the course even started:

- To begin with, a few informative e-mails indicating the solutions I had chosen and the links to attend and communicate (the link to my Zoom room where the course would take place; the link to the question sheet shared from Google documents; answers to questions on logistics).

- I also shot a small 2-minute video showing how to use Zoom from the student’s side, and giving some instructions for the class – for example, that all students mute their microphones to avoid noises in the background (reminder: almost all students are in confinement in apartments shared with other people, and possibly young children or animals…). It was also a test to see how easy it is to shoot a short video with Zoom => yes, it is easy, and it allows to relocate part of the content « outside of class ».

- Finally, I proposed to do a « trial run » two days before the course, i.e. a session of 15 minutes to test the technological solutions. Here again, and even if only 4 students were present, this session was very beneficial in bringing out the problems that can arise in a real situation.

- In retrospect, I see several beneficial effects from this abundance of communication. On a basic level, it sends the message that I am working for my students, and that they are not being left alone in this situation. On a less obvious level, it prepares the students for the online course experience, by giving them a few things in advance of what is going to happen (written communication of questions, sharing documents with online annotation…). And finally, maybe it can create a sense of committment, by convincing students to really attend the online course, instead of passively waiting for the recorded session for deferred viewing. In other words, it helps to make them a little less « passive listeners » and a little more « actors in their learning ».

- Coordination with colleagues. In the case of an online course, there is a lot of hidden time that does not necessarily appear as such. The coordination with my colleague for our 2 classes required several exchanges by email, phone calls and a Zoom training session. Once again, as obvious as it may appear, there’s a huge difference between intellectual knowledge (« you’ll see, Zoom is like Skype »), and the simulation of a course session (for example, thinking about launching the recording of the session 😉 ).

During class

This first experience was the opportunity to experience several discomforts.

- The key discomfort was to realize that during an online class, everything becomes extremely slow. Juggling between different activities adds each time a small amount of latency (« lag »), with the corresponding stress building up. What one does naturally in a physical classroom, without even thinking about it, requires much more concentration when doing an onlinecourse.

- For example, while displaying slides, you can grab a felt tip pen at any time and begin write on the board. Online, this means that you have to activate the annotation bar (lag), then choose whether you are going to type a text or draw, because it is not the same tool (lag), then click on the chosen tool, then draw on the slide above your text (lag), then select the eraser to erase the drawing (lag), then select the mouse arrow to return to the slide scroll mode (lag). Of course, in such a complex sequence, there are a lot of mishaps and idle times… In several occasions, I found myself scribbling on a slide when I wanted in fact to scroll to the next slide. So [select eraser], [delete], [select arrow], [scroll slide]…

- And yet, those are simple manipulations. Comparatively, it will take an even longer time to share a given document on the screen. In these cases, one of the lessons I have learned is to choose when (not to) apply the advice that radio hosts know: avoid silence on the air (« dead air ») at all costs. Indeed, when we fumble with controls or wait for a document to appear, we all tend to repeat the same words and excuses over and over again: « You’re going to have to wait a bit… », « Ah, it takes a while to load… », « Sorry, my computer is slow… ». In fact, it’s an attempt to fill the silence, without conveying any real information. So I suggest two alternative strategies:

- Silence. Please avoid try to fill the silence. Take advantage of this situation to breathe. Tell yourself that everyone has earned this silent break, both the teacher who stops talking for a moment, and the students who can relax for a while. A short sentence such as « take a deep breath while you wait » can even explicitly signal that it’s a mini-break.

- Moving into metacommunication. A strategy not to be used systematically, as it requires a minimum of preparation. This consists in commenting on the situation. For example, « as you can see, it takes time to load. Then again, you will often have the role to conduct meetings remotely. So my question is: which solutions would you use to avoid the discomfort of this waiting time and/or to continue to motivate your listeners? « It can also be « use this moment to take stock of what we have just said. If you had to summarize in a few key ideas what we’ve been talking about for the last 20 minutes, what would you write? »

- There’s also what I call the double lag.

- First, there is the technological lag: between the moment I draw on the screen and the moment it is displayed on the student’s screen, there is a lag that depends on the quality of our respective Internet connections and the power of our respective processors. This means that when I ask a question, it can take no less than 3 seconds, and often more, before the students actually hear it.

- And there is also the human lag. In a real-life classroom, when I ask a question, there is always a silence that follows. Indeed, the students have to process the question to understand it; then they mentally look for answers they might give; finally they decide whether they are going to participate to share their ideas, and if the answer is yes, then they start thinking about the form of their oral participation. All this takes time, which might depend on the students’ brain speed, but all in all, it is never negligible. That being said, even when this happens in a classroom, not all professors have the same reaction to silence. In my classes on pedagogy, I use the MBTI (Myers-Briggs) model to show that lecturers generally have a type of teaching that corresponds to their own personality type. For example, if we take the first axis of the MBTI model, type E professors will tend to expect a quick reaction from their students. Once they have asked a question, they have their perception of relative time, and they will begin to feel discomfort as soon as silence lasts more than a few seconds: they will thus tend to react quickly, either by asking the question again, or by rephrasing or cold calling a given student – who might still be in his/her thinking process.

- Now, in an online class, there is the cumulative effect of this double lag. Things take more time: even a simple conversation back and forth (« Are you okay? », « Yes, I’m okay! « ) takes a longer time online than in real life. So when it comes to more complex issues, with the effect of the double lag, it is better to learn to slow down real-life reflexes, to breathe, to get used to silence… This can lead to an « old and wise man » effect which is not bad. The students can feel that the rhythm becomes more relaxed, more reflective, and less oriented towards a dialogue in the form of a verbal ping-pong…

- The loneliness of the black screen. Online, most (and, in my experience, all) students turn off their cameras. So this leads to teaching black screens. You can’t tell whether the student is nodding his head, if she’s taking notes in a concentrated way, if he’s very busy with a parallel discussion through e-mail, or even whether she has left the room… This leads to moments of loneliness, when we call Jim who had typed a question and we all wait for Jim to unmute his microphone… or to come back into the room eventually. When this is combined with a low use of the Chat by students, it feels like talking to an empty room.

- All of this leads to a lot of stress and a lot of consumed energy. Compared to a face-to-face course (which is already a tiring experience, on a physical, emotional and mental level), an online course requires to send out a lot more energy, and to exercise a lot more control – while having, comparatively speaking, a lot less feedback. In this first course, for example:

- less than half of the students were connected

- the Google docs sheet intended to receive the questions remained empty throughout the class

- Chat was not used often, and when used, it showed its limits: when I ask a question, students think (double lag) and they want to type their answer quickly… at the expense of clarity! So I had some answers that were really difficult to use as inputs:

- on the one hand, you want to praise the student who took the trouble to write and interact (positive reinforcement);

- on the other hand, the message may not be understandable, or it may mean several different things. In short, it is a downgraded communication that can lead to frustration on both sides.

In my case, the demand for energy and concentration was further increased by the fact that this course is given in English, which is not my mother tongue… And even though I think I have a good level in English (at least enough to have delivered classes in this language for years), the online transition adds a difficulty because of all the unplanned elements. Let’s take an analogy.

- Let’s imagine that we tell a French manager that he’s going to have to make a presentation in English. So he prepares for it, he writes out his speech elements, the visual aids, and most often he repeats the speech in front of his mirror, he might even be timing his speaking time until he feels ready and in control.

- Now let’s imagine that the same manager is told that he will have to conduct a « fire and evacuation » drill in English. He doesn’t necessarily know the technical terms, because he is no fireman; he doesn’t know what will happen, who will interupt and when, or the nature of the questions that will be asked; he doesn’t especially have expertise in « fire evacuations ». In this second case, the experience of communicating in English will be much more demanding, both in terms of energy and concentration that are required.

To sum up, I felt like the nice Dr. Jekyll, used to an already well-controlled and comfortable life, who said to himself, « Even if I don’t know this new part of town at all, I just have to behave as usual ». Well, it’s not enough. It’s not enough at all. Hence the fatigue and frustration that came from this first experience in the form of a baptism of fire.

In the next blog post, we will see my next classes, and my progressive mutation into Mister Hyde… (work in progress 😉 )

“Here then, as I lay down the pen and proceed to seal up my confession, I bring the life of that unhappy Henry Jekyll to an end.”

Robert Louis Stevenson, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde